In this brief theoretical exploration, ENPA board member Panos Tsitsanoudis reflects on the importance of staying with the risks of interdisciplinarity on our epistemological horizons.

Seemingly, today, a desire for interdisciplinarity gains more ground among academic practices and institutions. But how are we getting closer with something that resists itself from being explained or eased? What kind of intimacies do we develop with the upsetting parts of interdisciplinary thinking? I aim to tackle these questions from the milieu of one of the most adventurous encounters of the 20th century: that of psychoanalysis and anthropology.

The historical conjuncture of psychoanalytic theory with ethnographic practices and anthropological research constituted a disquieting moment in regards with both disciplinary structures, while at the same time, it is in this intersection that both of them developed their theoretical grammars and their methodological lexicons (Terzakis, 2022). It’s interesting to think, how this encounter, of two structurally different disciplines (Crapanzano, 1992, p. 138) constituted a historical process of problematization that haunts both of them, till today.

Starting from the birth of the question of Oedipus, in the era after Freud’s (1913) Totem and Taboo, the first elements of a psychoanalytic anthropology, or what was further elaborated by the work of George Devereux as Ethnopsychoanalysis, came into existence. The “traumatic point” of the invention of Oedipus, gave to the encounter between the two “imaginary bodies” of anthropology and psychoanalysis, its full meaning (Smadja, 2017, p. 156). In the aftermath of this, the questions around cultures, psyches, and histories revolve around something that remains ultimately unresolved. Something in-between psychoanalysis and anthropology (and as a result, something in-between psychological and social sciences in the broader sense): the risk of interdisciplinarity.

Thinking on interdisciplinarity from the milieu of psychoanalytic anthropology can reactivate crucial theoretical and methodological challenges for our current intellectual practices between and beyond disciplinary borders. This act of reactivation seems very relevant today, when we can still see how different forms of knowledge remain unable to build a common ethical or epistemological gesture. It’s probably into an atmosphere of enthusiasm towards interdisciplinarity, where we can still see how a dialogue between different fields and forms of thinking tends to remain suspended. As I will try to discuss further, if we look closer to this paradox, we might see that the suspension is not operating anymore through the old fantasy of a hard disciplinary border that makes the dialogue impossible, but through a total neutralization of the dynamics of the dialogue as such, when every agonistic ethos of argumentation tends to be vanished. If this is a symptomatic point of how an academic style of communication is currently forming itself, then the quest of re/thinking interdisciplinarity brings us back to the question of how we inhabit our intellectual practices and research frameworks. Or even more: what we want to do with them.

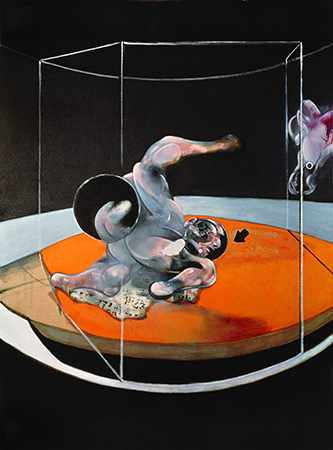

Francis Bacon (1976). Figure in Movement

All of these remain a pressing question, for most of us, who already craft their methods and theories, in liminal places between disciplines. Looking back to George Devereux’s work and his intuition to move “from anxiety to method” (Devereux, 1967) we will meet similar issues of concern (Jackson, 2010). More specifically, Devereaux attempted to walk this slippery path of interdisciplinarity by constructing a complementary framework of reference between psychoanalysis and anthropology (Devereux, 1978). As if he had already felt the potential risks of this crossing, his main concern was: to make any reductionism seem illusory (Stitou, 2016, p. 1661). Following his thought, we can see how he didn’t aim neither at a negation of each discipline’s epistemological autonomy nor at a neutral complementarity of merging different elements from both fields together. Complementarism as an ethnopsychoanalytic method can be framed as the process when “one form of knowledge bears out its inconsistency” and “another form of knowledge can in some sense take over” (Gouriou, 2012, p. 214). The sensitive zones between them, constitute the thresholds of passing from one to another. These opaque areas constitute their common. It’s exactly in these areas that interdisciplinarity emerges as a potential. When these areas are being dismissed, the object of research can be devoured by researcher’s or analyst’s interpretation and finally, get destroyed. The common ground that enables interdisciplinary thinking lies in the zone of opacity between a discipline and its object, that is to say, between an anthropologist and his informants (Crapanzano, 2010, p. 63) or between a psychoanalyst and her patients (Saketopoulou, 2023).

Thus, we can see how Devereux’s early methodological theorization, proposed a cut of a different nature: an ethicopolitical critique regarding the ways that we approach a field of research. His gesture towards a research ground that is risking to exist between disciplines resists the psychologization of cultural and societal phenomena, while it simultaneously remains an obstacle to the sociologization of the unconscious psychic imprints, or the idiosyncratic idioms of oneself (Devereux, 1970). What lies in the heart of Devereaux’s thought, is something raw: something that is not a property neither to psychology, nor to sociology, or anthropology (Devereux, 1978). Something that escapes them all, and it’s only in this way that becomes a common. Something that can only be later examined as psychoanalytic or anthropological data but nevertheless something that is evidently enigmatic and opaque (Saketopoulou, 2023, p. 155): the irreducible condition of every encounter, every element or every field that we are living in. This area that can’t be appropriated by any discipline remains always the undecidable zone (Gouriou, 2012) in-between disciplines. The different tropes of interactions that we develop with this zone are constitutive of our epistemological capacity to interdisciplinary thinking.

In the same way, from a psychoanalytic anthropological point of view, there is something irreducible between the idiosyncratic idioms and the social or cultural predicates of oneself (Gouriou, 2012) or between an idiosyncratic and an ethnic unconscious (Devereux, 1970). Deveraux tried to describe the ways that a symptom is always embedded into specific historical and cultural contexts and thus, it is always formed through a process that draws the lines between the conscious and the unconscious, the normal and the abnormal (Devereaux, 1970). By describing this psychization of cultural phenomena, he constructed a theory of a psychocultural unconscious in order to describe the ways that cultural materials obtain different psychic uses (op.cit, p. 123). In these crossroads of analysis, we are coming to face again the challenge of what kind of questions we want to ask (Deleuze & Guattari, 1975, p.182), as researchers, anthropologists and/or psychotherapists, psychoanalysts. How will we formulate our questions along these delicate lines between the violent reductionisms of culture or society and the essentialism of the psychologized self? Given the fact that empirically, someone never encounters neither cultures, nor individuals (Jackson, 2010, p. 52) but something more than this, the question of how we are approaching a field of research, remains far more important than the question of what this research is about.

Similarly, we can see how the questions occurring in interdisciplinary crossings between psychoanalysis and anthropology reflect in fact, questions that exist already into each one of them. In a way, to bear the discomforts of interdisciplinarity means, to walk with the intensities of research, as such. To relate with them, without compromising them, requires the building of a framework of listening to the multiple and unnamed elements of psychocultural life. Ethnographic and psychoanalytic practice always refer to a sensibility of listening as a way of undoing different certainties and enable more articulations. In this sense, the tensions between psychoanalysis and anthropology, or between psy-sciences and social sciences at large, can remain productively unresolved, as long as this constitutes a process through which we are growing a capacity to stay with the trouble of listening. A process, that inevitably problematizes our knoelwdge through the continuous unfolding of different forms of questions. That’s exactly how we would describe a psychoanalytic session or an ethnographic research process: you keep revolving around something that remains unfinished (Stewart, 2007).

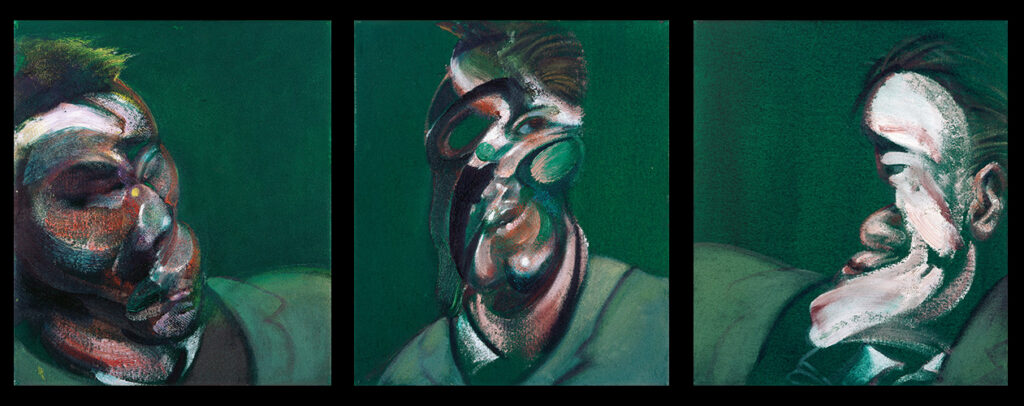

Francis Bacon (1967). Three Studies for a Self Portrait

It is the presence of a foreign element (Stitou, 2016, p. 1668) contained into the challenge of interdisciplinarity, that can ex-cite us (Saketopoulou, 2023, p. 30), fuse our epistemological horizons, discomfort us, “set us in motion” (op.cit). My proposition, here, aims at a research ethos of listening rather than solving, in the same way that Avgi Saketopoulou writes about trauma, as something that we need to keep open to its unexpectedness (Saketopoulou, 2023, p. 133). Something that never really closes, because it is fugitive (op.cit, p. 134); something that re-opens, because it needs to ‘speak’ more. It’s exactly this motor factor of psychic life that exceeds every scheme and interpretation. From this ethical standpoint, we might be in the position to form the question of how we will become able to organize our research and theoretical aims at the level of this “play” (Crapanzano, 1992, p. 152) that occurs in every human and non-human interaction. That play, which formulates “a not yet that fringes every determinate context or normativity with a margin of something deferred or something that failed to arrive, or has been lost, or is waiting in the wings, nascent, perhaps pressing” (Stewart, 2007, p. 80).

The risk of interdisciplinarity inevitably corresponds to a not yet, that defines both psychoanalysis and anthropology. It’s a risk inscribed in this position of developing a certain intimacy with the “terrifying possibility of otherness” (Crapanzano, 1992, p. 139). In the face of an ongoing ethicopolitical flattening that tends to eliminate this discomforting possibility inside and between our disciplines, the development of a methodological and theoretical reciprocity to the “agonistic dimensions of the dialogue” (Crapanzano, 1992, p. 141) remains of critical importance. Afterall, if there was something in the history of psychoanalytic anthropology in which the encounters with the zone of opacities (Saketopoulou, 2023, p. 3) became possible, that was the dynamics of risk. Eventually, it is now, more than ever, that we need to stay at risk (Crapanzano, 1992, p. 139).

Panos Tsitsanoudis is a doctoral candidate at the Institute for Social and Cultural Anthropology, Freie Universität Berlin. His research focuses on the psychological discourses that shape the discussion of femicide, intimacy and death in Greece. He holds a BA in Psychology from the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki and an MA in Gender Studies from the Department of Social Anthropology and History at the University of the Aegean in Lesvos. His research methods and fields vary between psychoanalysis, critical psychological anthropology and critical discourse analysis.

Leave a Reply