In our second post in the “An Interview With..” series, we introduce one of our blog team members Maija Sequeira. She also shares some of the photos from her PhD fieldwork.

What are you currently researching?

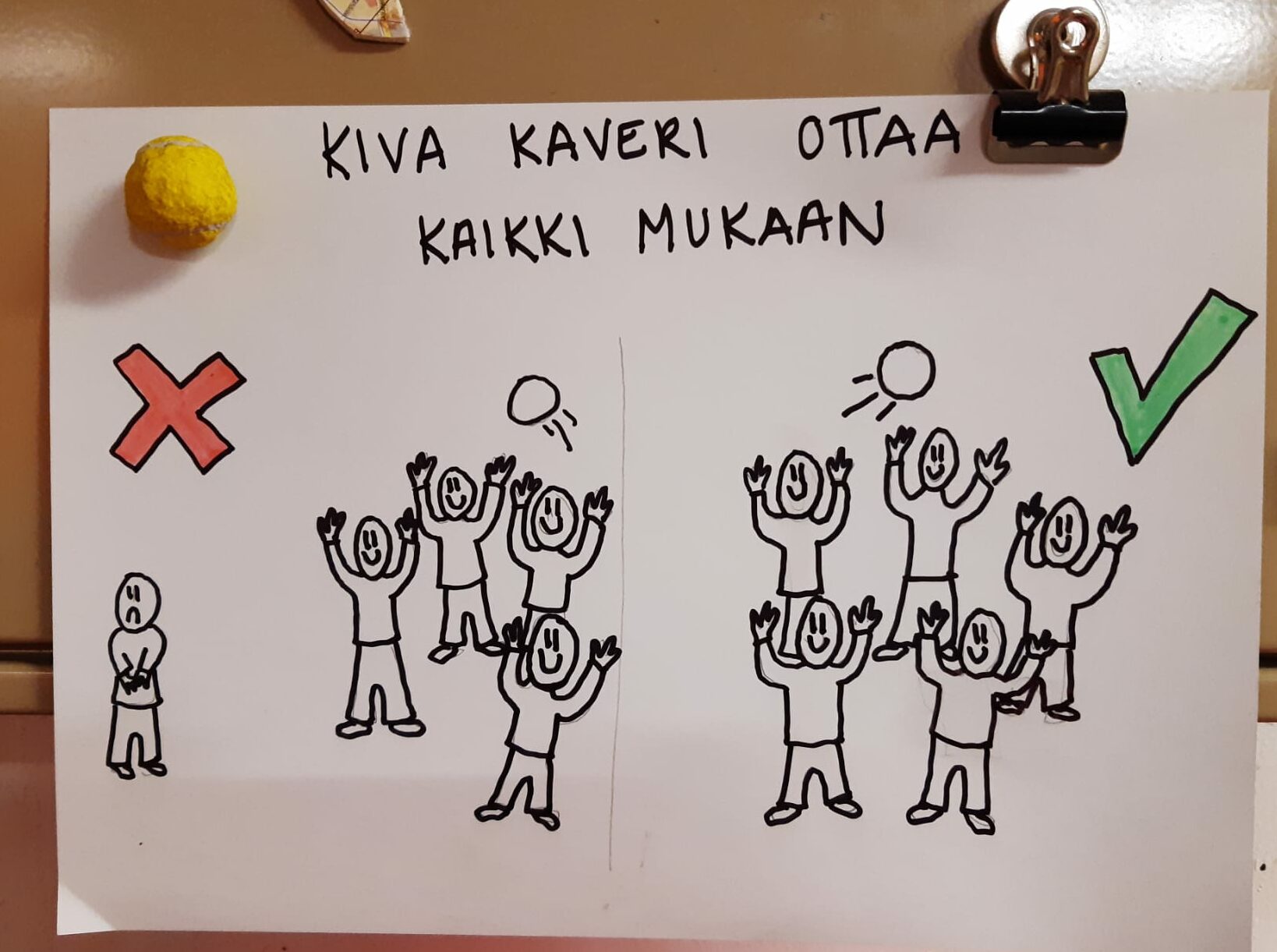

In my PhD research, I am trying to understand how the socio-cultural environments within which children grow and are socialised shape how they understand social hierarchies. I’m conducting research in two extremely different cities – Helsinki, Finland, and Santa Marta, Colombia – and am (1) quantifying the differences in Finnish and Colombian children’s understandings of and preferences for different hierarchy-related processes, particularly dominance- and prestige-based strategies, by conducting a series of experiments with children in each setting, and (2) using ethnographic methods to explore and understand how these differences are shaped by specific norms, values and found in their socio-cultural environments.

Why did you choose this area of study?

I have an interdisciplinary background in Human Sciences and have always been interested in humans as a product of both ‘nature and nurture’, as it were. I’m interested in how childhood socialisation varies in different contexts and the consequences of this on both an individual and a macro level. I have spent most of the past 5 years working and living with children in a range of different ways – as a volunteer, teacher, camp leader and aunt – and find them fun and interesting to be around. Seeing how children are raised, educated, disciplined and socialised into and within different societies and families is endlessly fascinating and forms the basis of my interest in cross-cultural studies on childhood.

How will your research improve or have a wider impact on society?

I think one very interesting thing that will come out of this research is a deeper understanding of how an individual’s early life experiences and socialisation serve to shape not just their understandings of hierarchical relationships, but also what types of leaders they prefer and what they expect from leaders. There is evidence that dominant leaders are particularly favoured in situations of resource-inequality [1], and I hope that by carrying out comparative analyses between Finland – known globally for its relative equality and stability – and Colombia – one of the world’s most unequal countries, with a long history of civil unrest – I will be able to identify particular norms, values or structures in each society that influence and shape the ways in which children learn important ideas about ‘what a leader is’ and ‘what a leader does’. These expectations and preferences – learnt from a young age – are likely to have very real repercussions at a societal level through, for example, the ways that they shape voting behaviour, the demands that individuals and civil society make on their leaders, and the probability that they will hold leaders accountable to their actions.

In a few words, what is the best thing about your field(sites)?

It’s fun! I spent the summer of 2021 on camp with 7–13-year-olds, and they managed to surprise me every single day. It was exhausting but ridiculously fun to be allowed (back) into the world of water fights, dance battles, endless football and volleyball matches, handstand competitions, wink murder, stickers, friendship bracelets and everything else that filled the children’s days. It’s also wonderfully rewarding spending time with children as an anthropologist, rather than as a teacher or someone who is trying to ‘get something done’, as they tend to respond so positively to an adult who is actually interested in what they have to say.

What is a typical day of fieldwork like for you?

The past year has been a whirlwind and my typical day has changed drastically every few months or so, as new opportunities have opened up. The first months of 2021 were quite slow-paced, as I started out making connections with local families and community groups, visiting a handful of people’s homes and spending time with children and families in any way that I feasibly could, while also trying to follow and respect the pandemic-era restrictions and recommendations and my own ethical obligations. I also dabbled in online ethnography at this point and I attended some birthday parties, music groups, toddler meet-ups, and anything and everything that I could get an invite to during this time – while still hoping (against hopes) that I would be able to get access to a school at some point during the year.

By the summer, things were relatively normal in Helsinki, and I was lucky enough to go on 7 weeks of summer camp. This meant 24/7 access to – ie. no escape from – up to 80 children at a time, as they (we) camped, swam, played, ate, fought, and laughed their (our) way through camp. Those weeks were wonderfully intense; I was exhausted just from the day’s activities, let alone from then trying to find some quiet time to write, so it often felt like I didn’t have time to absorb and note down everything that was happening. Looking back at my notes now, however, they are full of fascinating patterns and interesting observations that spark off all kinds of frenzied article searches. Finally, during the autumn term, I went to a daily after-school club, where I got to know a smaller group of first and second graders (aged 7-9 years), spending time with them between their school day finishing – often as early as 11:30 am – and them going home. This calmer, longer-term investment in the same group has been the perfect complement to the intensity of camps since I have been able to follow the children’s relationships for several months and get to know them on a more personal level.

What are some of the biggest challenges you’ve faced in your research or career?

Unsurprisingly, starting my fieldwork mid-pandemic has been the biggest challenge so far. I’m lucky that I have very supportive supervisors and funders and was able to adapt my project to the circumstances without its essence changing too much – but the uncertainty has been difficult to handle sometimes. I had flights to Colombia booked for January 2021, then for August 2021, and now I am hoping to be able to go in August 2022, which has made planning my work – and my private life! – quite difficult at times. However, I am very privileged in that the pandemic also sent me down some paths that I don’t think I would have otherwise explored. For example, I was able to try out online data collection methods, and I think the data I got from camps and after-school clubs is much richer than the data I would have collected from schools. As a result of not being able to travel myself, I’ve also been forced to develop a more collaborative project, working closely with researchers at the Universidad de Magdalena in Santa Marta to conduct the experimental aspects of this project locally.

About the Author

Maija is a PhD student in Social and Cultural Anthropology at the University of Helsinki, Finland. She is also on the ENPA blog team.

You can find her on Twitter @maija_eliina.

Leave a Reply