In this blog post, Jane McNulty reflects on the ritual experience of attending the funeral of someone who she had been close to in her youth. Her ethnographic description evokes cultural aspects of the community in Northern England and her own psychological ruminations on belonging.

By Jane McNulty

In April 2018, I attended the funeral of someone I’d known many years ago. As the deceased’s first girlfriend, I was invited to Lance’s funeral by his only remaining brother, Dean, and by Janice, Lance’s last girlfriend. Despite having seen Lance only once since 1976 when we were both teenagers, I wanted to go, and as Janice seemed quite OK about the arrangement, that seemed to seal the approval on my being there.

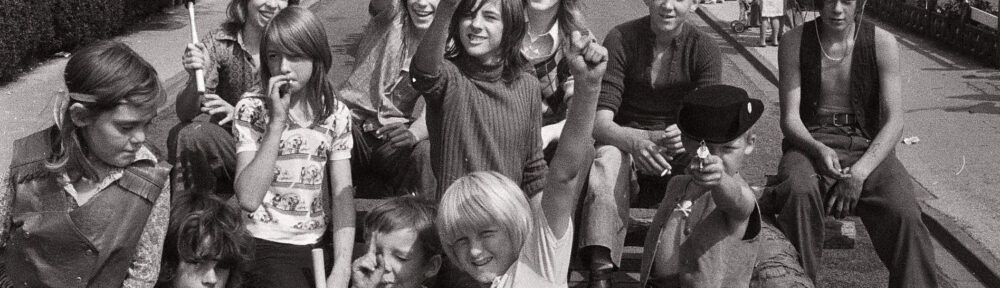

Lance’s family had lived on the outskirts of Greater Manchester, in one of the biggest ‘overspill’ estates in the country at the time. Despite it also being one of the most economically deprived areas at that time, there was that strong feeling of community, the sense that ‘we’re all in this hole together’ way of life. The same can be said with death. The ritual of funeral strengthens that bond, brings people together. Funeral rites are significant to a community’s sense of identity. Identity is important too, who you are and where you fit in is a question that comes up time and again in my memory of this day.

The funeral party assembled at Lance’s house to wait for the hearse, and for the car for the chief mourners. Lance was poor. He’d had a chequered work history; odd jobs, spells on sickness and unemployment benefit, years as a full time carer for his mother. He had no savings, no reserves: his girlfriend had a life-limiting illness and lived on sickness benefit. Lance had lived in the council house where he was born up to his death: he’d never married, he had no children. Between his death and the day of the funeral, friends and family had cleared the house, scrubbed it – someone had rehomed the dog – as the council were asking for the keys. Assembling at the empty house was very strange, but there were glasses for the cans of lager, the tots of whisky, the glasses of wine for the funeral goers who needed a drink to steady their nerves (they brought their own, none was provided) as we waited for the funeral cars to arrive. People stood in the front garden smoking, drinking, talking. They were dressed in black, despite the baking heat, men and women alike. The younger men took off their jackets. Children ran about in their best clothes. Neighbours watched from their front doorsteps.

The funeral cars arrived. Dean and Janice, with her sister and daughters, a favoured son, and a favoured grandchild, took up seats in the family car behind the hearse. The coffin was flanked by floral tributes made cheaply by a local woman. Janice presented red roses in a black ‘box’ arrangement; a white floral arrangement spelled ‘Pops’ (Janice’s grandchildren’s name for Lance.) My spray of six white roses, having been bought from the funeral directors direct, was on top of the coffin. Everyone piled in their cars, and the funeral director, wearing a frock coat and foreshortened top hat, walked for 100 meters in front of the hearse as the mourners’ cars formed a line behind. She then hopped into the hearse and we all drove, at the speed limit (at one time funeral corteges would go at a respectful 15 – 20 mph), the three miles through county lanes to the crematorium.

The hearse and family car waited on the road while the rest of us parked up. There were about 60 people in attendance and we hung around the entrance to the crematorium, a low, brick building with a chimney, where we renewed old acquaintances and sneaked a quick smoke, until the hearse finally pulled up to the door and the back doors opened. Bearers carried the coffin in, and the mourners followed in order – Janice and family first, with Dean, then cousins and friends. I hung back, I didn’t feel I belonged.

The room where the committal ceremony was to take place was set out like a small church, with rows of seats split by a central aisle, a lectern at the front, and to one side a bier on which the coffin was placed. There were vases of artificial flowers but no religious symbols. The celebrant, oddly wearing a purple cloak, stood at the lectern while the mourners took their seats, Dean and Janice and her family on the front rows. I chose a seat half way down, by a high window of frosted glass. There were printed ‘orders of service’ on the seats detailing Lance’s dates of birth and death, the programme of music and readings, and a photo of him that, in the absence of any other photos, I’d provided. It was a school photo Lance had given me, aged 15, when we first knew one another. He’s fresh faced, smiling. Music played as we settled, Jimi Hendrix’s version of The Star Spangled Banner, Lance’s choice – not a traditional or usual one – and some people giggled, some murmured approvingly, ‘just like him’ etc. No one cried.

The celebrant spoke about Lance’s life, his exploits, his wildness, his love of dogs, his love for Janice and her children and grandchildren. I didn’t recognise the man he spoke about but it had been a long time…. Then there was another piece of music (the Moody Blues’ Tuesday Afternoon) and a poem. There were no hymns or prayers – Lance didn’t believe in God or religion and had requested no religious trappings. As the curtains closed on the coffin – the congregation aren’t to see the coffin jerk away on rollers towards the trapdoor to the furnace room beyond – a last piece of music was played, Islands in the Stream by Dolly Parton and Kenny Rogers, and finally someone cried. I think it was Janice.

Outside, in the blinding sunshine, mourners gathered to shake the hand of the celebrant and to speak to Dean and Janice (‘great service’, ‘loved the music’, ‘see you at the Workers’ etc). The floral tributes were laid out on the flagstones at the back of the crematorium. Janice’s son came and collected up their flowers to take home, not something I’d witnessed before at a funeral. I left my white roses – they were wilted anyway.

We all decamped back to the Working Men’s Club in Lance’s hometown. There was a crush at the bar as everyone got much needed pints and wine and shorts. The mourners sat around, any tension now gone, and had a laugh, remembering Lance and others that had died, remembering their own lives. Pies and sandwiches appeared but drink was the order of that hot afternoon. A vegetarian tee-totaller, I had a glass of water. The man, someone who’d known Lance somehow and who I’d been asked to give a lift to the funeral service asked if I wanted company. I wanted to be on my own with my thoughts but that seemed to cause concern, so I joined him and two of his friends. Dean and Janice and other mourners were drinking, nipping out for a smoke, drinking more. I made my excuses and left. On the way home, I made a detour past the places I associated with Lance from our time together. I may have cried.

I’m from a working class background, albeit from the opposite side of the Manchester Ship Canal, but my family were slightly better off than those attending Lance’s funeral. As a writer and university tutor, I may be perceived to have ‘moved up a class’, and no matter my roots and how well I knew some of the mourners back when Lance and I were friends, I felt out of place. Not drinking has something to do with that, I am sure, and the vegetarianism contributed – my refusing ham sandwiches raised eyebrows – but it was a strange and uncomfortable experience. Where once, forty five years ago, I would have felt at home, now I felt like the outsider. Can you ever go back?

A funeral ritual is important in most cultures, and differs from culture to culture, community to community. This was in a poor, working class (is there such a thing as a benefits class? I think so) community: money for the funeral was tight but there is a strong tradition of ‘a good send off’, that rites must be observed – flowers, and in particular the name or title of the deceased spelled out in flowers; a hearse with attendants in suitable clothing; a limo for the bereaved family members; respectful observance by the neighbours as the cortege assembles; the attendance of as many friends and family as possible at the funeral (one man was prepared to walk the three miles from the house to the crematorium, as he had no car) the wearing of black clothing by mourners, even on the hottest of days; music chosen by and representative of the deceased, where possible; a suitable amount of public weeping; plenty of drink available afterwards. All these matters must be observed if a ‘good send off’ is to be achieved.

But funerals are expensive, even basic ones. This funeral cost, I understand, around £2,400 which is cheap by comparison to average UK funeral (cremation) costing £3,700, but even so, it was beyond the reach of Lance’s family. Dean opened a ‘gofundme’ type appeal and most of the funeral costs were covered by donations from friends. I believe that, as the price of funerals continues to rise, this type of group funding for funerals is increasingly common. There are cheaper options – one local funeral director offers a basic cremation for £950 and these are often funded by local authorities under their statutory duties, however at these events no one from friends or family is allowed to attend. This seems cruel and harsh punishment for being poor. No wonder then that the friends and family of those who die without funds are increasingly rallying round to cover the costs of ‘decent’ funerals.

It is important in our society, as in every other, that everyone should have a decent funeral. The last ceremony marking a person’s life should be attended by as many as possible of those with a connection with the deceased. This event marks the deceased as having had significance in life and worth, even in death. It also reinforces our own desire to be remembered beyond our own deaths. We need to feel that the person’s death has, for a brief few hours, stopped the everyday business of life and work, enabling everyone to pause and reflect on the dead person, their own relationship with them (is there any ‘unfinished business’ between them that, at the funeral, can be put to rest?) and the unhappy vision of their own fate. Hopefully, by being present at this funeral, the mourner can help guarantee a decent crowd in attendance at their own. The drinks and chat afterwards, the laughter, the dancing (at Lance’s ‘after funeral drinks’ I saw a few people dancing to the club’s piped pop music) all serve to remind us that life does go on, and that no matter how sad we are to be at the passing of our friend, we can all enjoy a drink and a good time before our time comes to pass.

About the author

Ane McNulty has lived all her life in Cadishead, on the north bank of the Manchester Ship Canal, although she did a lot of her growing-up as a teenager on the south side in an overspill estate-cum-village called Partington. Her love affair with Partington and its people has continued throughout her life.

For several years Jane worked as a scriptwriter for TV series drama, before discovering a love of theatre. She has toured three original plays to date and has just completed a piece of musical theatre, writing both book and lyrics. She has recently been diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease.

Leave a Reply