In this post, ENPA Convenor, John Loewenthal explores how training to become a therapist could make for a truly anthropological career.

I recently spoke in a panel, ‘University Admissions and Careers with Anthropology: Your questions answered’ at London Anthropology Day (LAD) 2023. LAD is an annual event aimed at introducing people to anthropology, primarily adolescents, though also their parents, and prospective postgraduate or further education students. The day features a range of stalls and talks with a focus on university study and the offerings of different courses. Like all those speaking at LAD, I carried a moral responsibility regarding the futures I was endorsing. Carr (2006) highlights the ethical responsibility of teachers and persons who have the potential to influence young people and the trajectory of their lives. Anthropology is a notoriously non-vocational degree. The lack of a specific graduate outcome may cause concern, and be a risk, for university applicants. Such prospects may be especially off-putting for persons of various cultural and class backgrounds who, along with their families, wish for more economic assurances from higher education. Even noble aims of widening participation to anthropological study and academic careers (Mills, 2021) could risk leading young people up a precarious garden path. Parents and others may ask, what can you do with an anthropology degree?

The question is warranted. Ilana Gershon (2015) describes how difficult jobs are for her anthropology students to imagine: “I have so many students who don’t know what they want to do when they graduate, who don’t even know what kinds of jobs are possible. They think mostly of the jobs that their parents and their parents’ friends have, or the jobs that they see on television. They often wonder how to even begin to dream of other ways of living, of other kinds of work that they would enjoy” (p. 9). My doctoral research was on the aspirations of university graduates, where I encountered a similar difficulty for people to imagine possible careers, not limited to students of anthropology. As Brooks (2015) writes, “Many young people are graduating into limbo. Floating and plagued by uncertainty, they want to know what specifically they should do with their lives” (p. 14).

My aim, in speaking at the careers panel at LAD, and writing this blog post, is to flag counselling and psychotherapy as one possible career path for anthropology graduates. I believe that the trajectory is very intuitive and yet under-represented, compounded by unclear pathways into the world of therapy. I hope to render this career path more visible, even if (prospective) anthropology students only consider it years down the line. Extending beyond LAD, I hope to contribute towards establishing a better-defined pathway that connects anthropological study with therapeutic careers. Hopefully, doing so can help some anthropology graduates to apply their learning about human beings and to find a vocation that keeps them moving in the same direction. A stronger bridge from theory (or study) to practice also reaffirms the value of anthropology and its applied capacity.

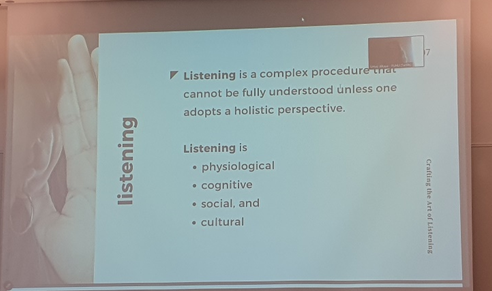

I am currently training to become a therapist and find it to be extremely anthropological, as well as life-affirming and both intellectually and relationally stimulating. Therapy training asks students to practice their listening and responding skills through practice sessions in which students share their lives with each other. In my foundation year, a Certificate in Counselling Skills, I experienced the profundity of having fellow members of society of different ages and walks of life open up about aspects of their existence. In my current Diploma, we continue to take turns as Speaker, Listener, and Observer, sharing personal concerns. These issues, equivalent to those raised in therapy (though potentially lighter in nature), are often private, undisclosed to others, and even mysterious to the person sharing. The act of self-disclosure, as a means towards self-discovery and self-knowledge, aligns with the educational and existential goals of therapy, which aim to facilitate clarity and meaning in a person’s life (Egan, 2014). Therapists establish a connection by listening attentively and showing empathy. Accordingly, people invite you on intimate journeys into their inner lives and the intricacies of their social world. Therapists engage with people about their inter-subjective and intra-subjective experiences, equivalent to the nuances of conducting ‘face-to-face’ ethnographic research (Irving, 2017). It is worth warning that empathy can have its limits and drawbacks, such as burnout and vicarious trauma. I am also endorsing the profession while still only a part-time student and novice. Nonetheless, it would seem that with the right self-care, therapists can form a close connection to human beings on a day-to-day and week-to-week basis and have an endlessly ethnographic life.

Since attending LAD as a 17-year-old in 2009, the careers that I have heard mentioned as possibilities after studying anthropology have not included counselling and psychotherapy. Career options have tended to indicate that anthropology specialises in the study of culture and society and hence helps in providing cultural understanding and addressing social issues. Quoting Albert Piette (2015), I reminded the LAD audience that anthropology – further to studying culture or society – is a study of human beings: “How powerful, how intellectually liberating… to observe and compare people in the process of living and existing, either alone or with others, whether children, the elderly, the sick, the dying, or whoever” (p. 15).

I flagged psychological anthropology as a sub-field and mentioned two of its foci. These were person-centred approaches, studying “the complex interrelationships between individuals and their social, material, and symbolic contexts” (Levy and Hollan, 2014, p. 296) and the cross-cultural study of psychological theories (Quinn and Mageo, 2013) and therapeutic practices (Martin, 2019). I mentioned the recent gatherings of the European Network for Psychological Anthropology (ENPA) at the University of Oslo. There, such ideas were discussed in a convivial atmosphere amidst the everlasting Norwegian sun.

Research is important and reflects one possible anthropology career. However, not all anthropology undergraduates can or should follow such a route. Among other things, there aren’t enough university jobs, as MacClancy (2017) notes in exploring the contributions anthropologists can make to working in public service and government. Fellow anthropology graduates in this year’s LAD career panel discussed their exciting roles in design, business, filmmaking and academia, all employing anthropological thinking in different ways.

Adding to this list, I argued that counselling and psychotherapy are an applied form of anthropology. Therapists listen to people. They take their life and their concerns seriously, and make them feel recognised. Through empathy, they walk in other people’s shoes, including bracketing and working through their own prejudices and assumptions. Therapists think analytically and apply theory to try to make sense of people’s circumstances. They enter into a therapeutic relationship that is trusting, collaborative and nurturing. Therapists offer emotional support and verbal feedback, as well as light challenge, to help people to grow and to develop new perspectives about themselves, their relationships, their pasts, and their futures. There is something very meaningful about having genuine conversations about people’s problems and aspects of their personality that might be difficult for them to express elsewhere. Therapy is a privileged space to give these issues the attention and love they deserve. In doing so, therapists can achieve the elusive ideal of having a positive impact on people’s lives through their work.

The British Association of Counselling and Psychotherapy have a helpful careers page explaining routes into the profession (in the UK). People can train at any age, and will in fact be better suited as they gain maturity and life experience. This forging of a career (long) after one’s adolescence should hopefully eschew anxieties foisted upon young people to have their lives neatly planned from early on. In Britain, at least, one does not need an undergraduate degree in psychology to become a therapist. The routes are open via adult education and postgraduate diplomas and degrees. For good and for bad, postgraduate study is an increasingly normal and necessary means of gaining access to specialised professions (Collins, 2019). Considering this prospect of later specialisation, there is a strong argument to make the most of an undergraduate degree for its educational potential in opening horizons and cultivating character. While students could go straight into the psychological therapies from a psychology degree, why not first see the world through anthropology? Studying how and why people live as they do around the world provides students with a critical eye towards the social and material contexts, the cultural norms and beliefs, and the historical, political, and economic foundations through which people live. Anthropology teaches you to pay attention, to have empathy for difference, to have enthusiasm for being alive, and to see everything as a subject of curiosity. If graduates want an anthropological career of speaking intimately with people from across society and taking an interest in their lives, then it might be worth considering (one day) training to become a therapist.

About the Author

John Loewenthal is a Co-Convenor of the European Network for Psychological Anthropology. He is a Teaching Fellow in Education at the University of Edinburgh and currently studying for a Diploma in Relational Counselling (Integrative modality). He previously studied a BA in Archaeology and Anthropology, an MA in Anthropology and Education, and a PhD in Education, with a thesis ‘Aspirations of university graduates: an ethnography in New York and Los Angeles’. He is currently interested in counselling/ psychotherapy as a form of both anthropology and education.

Leave a Reply