Reporting from Kazakhstan, Julia Khan shares her continuing work promoting psychological anthropology with wider publics.

When we imagine what public psychological anthropology might look like, we often picture anthropologists doing fieldwork collaborating with communities, shaping interventions, or co-producing knowledge in clinical or educational settings. This summer, I found myself taking a quieter, less visible path. Unable to return to the field or initiate grassroots programs, I worked behind the scenes as an organizer of a national psychological forum in Kazakhstan, one of the few spaces where institutions openly discuss childhood, development, and education at scale. Instead of speaking from the margins, I placed an anthropological insight where it’s rarely expected: in the center of policy conversations. In a country where anthropology still echoes with its Soviet past concerned with categorizing ethnic types and fixing normative ideals, how do we make space for the invisible, the affective, the relational dimensions of development that psychological anthropology takes seriously? Perhaps, we start from the top.

On June 3–4, 2025, the II International Psychological Forum, titled “Modern Technologies for Diagnosing and Developing Children’s Abilities: Experience, Challenges, and Prospects”, was hosted at the Astana International Financial Center by the Kazakhstan Corporate Foundation El Umiti, featuring the psychological service Qabilet. The event brought together high-ranking government officials, educators, and mental health practitioners from across Kazakhstan and overseas. It focused on emerging technologies and theories for identifying and developing children’s abilities, framing ability as a measurable, trainable, and scalable attribute of the future national citizen.

Kazakhstan, a post-Soviet country that gained independence in 1991, has undergone a sustained project of nation-building reviving the Kazakh language, rewriting national history, and imagining youth as the vanguard of modern progress. Since the early 2000s, the country has experienced what Tomas Matza described as a “psychotherapy boom,” where psychological discourse has grown rapidly, particularly in education and parenting. This boom coincided with neoliberal state reforms, where psychological well-being and cognitive development became tied to entrepreneurial potential and human capital.

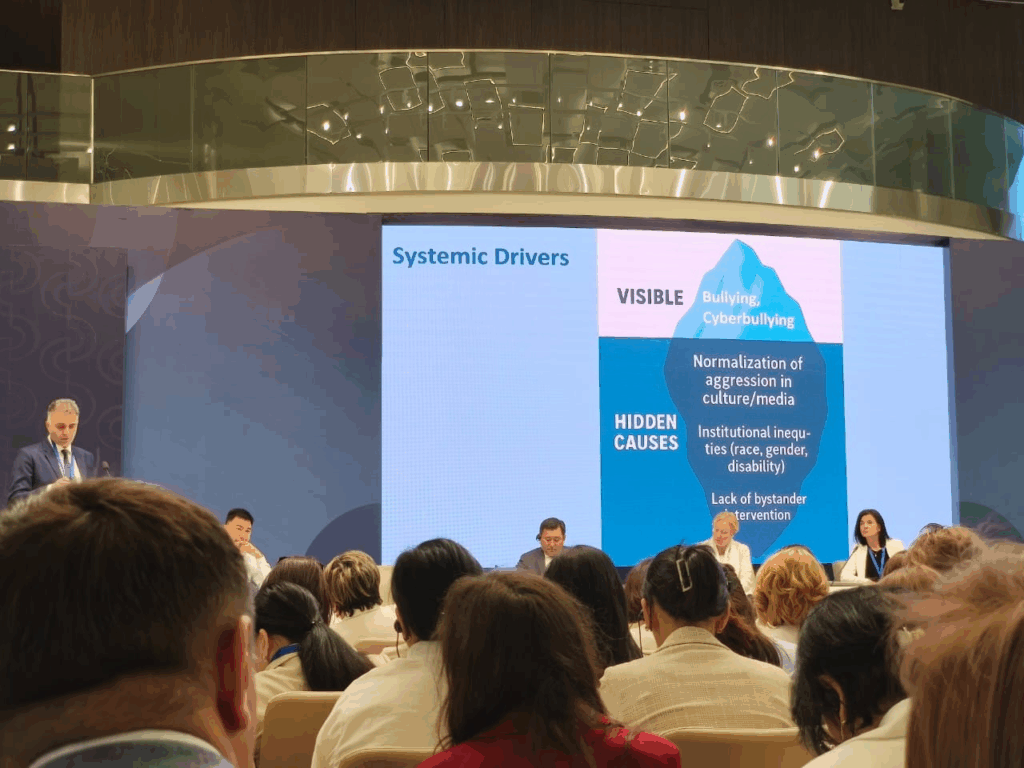

At the Forum, this was reflected in a focus on imported psychological theories particularly around secure attachment, standardized IQ and EQ measurements, and neurocognitive optimization. Children were often described in mechanistic terms: as brains to be trained, futures to be engineered. Missing from this conversation was a recognition of how deeply cultural meanings shape developmental pathways, and how local understandings of ability, discipline, and intelligence may differ from the dominant biomedical and educational models.

As one of the organizers of the forum, I had the opportunity to invite international keynote speakers on the forum’s theme, and I was determined to find an anthropologist whose voice would truly be heard. Through the generous introduction of Professor Kathleen Barlow (Central Washington University), whose work on child development and cultural learning in Papua New Guinea illuminates the deep interconnections between caregiving, emotion, and socialization, and my former supervisor Professor Hyang Jin Jung (Seoul National University), who explores the interplay of culture, self, and emotion in both Korean and American contexts (and who was once Professor Barlow’s student) I was able to invite Professor Thomas Weisner (Professor Emeritus, UCLA Departments of Anthropology and Psychiatry), a leading figure in psychological anthropology whose work emphasizes the role of culture, family, and daily routine in shaping child development. In a way, this invitation carried a quiet sense of lineage a thread of care, insight, and commitment to psychological anthropology that spans continents and generations.

In his talk, Professor Weisner offered a powerful reminder that ability is not a universal metric, but a context-dependent, relational experience. Drawing on decades of cross-cultural research, he spoke about the diverse ways children thrive within different caregiving systems, values, and educational expectations. He argued that without attention to cultural context, developmental interventions risk becoming alienating, ineffective, or even harmful.

His talk resonated not only among academics, but also among educators and policy-makers, who were lively discussing its implications in the corridors between panel sessions. Perhaps more importantly, Professor Weisner’s contribution paved the way for a new kind of conversation: one that recognizes the need for anthropological inquiry into local theories of child development. In the days following the forum, we began to explore a future possibility for a collaborative research project that would examine how ability, childhood, and success are understood within Kazakhstani families, schools, and institutions and how these meanings intersect (or clash) with globally circulating psychological models.

To me personally, this experience marks a small but meaningful step toward establishing psychological anthropology as a public-facing, policy-relevant discourse in Kazakhstan. It showed that there is always space for cultural perspectives, even within the technocratic frameworks of educational reform and economic development. Psychological anthropology is not yet known or institutionalized in the country. But, as any developmental specialists would agree, baby steps matter.

Julia Khan recently earned a PhD in Cultural Anthropology from Seoul National University and an MBA in Counseling from the Russian Institute of Practical Psychology. She is a Principal Investigator for projects on child development under the Kazakhstan Educational Foundation, El Umiti. Julia is interested in how global discourses on mental health, selfhood, and relationships shape educational practices and national policies in the post-Soviet region.

Leave a Reply